Fred Knauf, a member of the FFLA (Forest Fire Lookout Association), is an avid historian of all things fire tower related. During May and June 2019 Fred posted on the FFLA Facebook page a history of the Aermotor tower including the process of bringing the towers to their mountain tops. These posts were published on three consecutive Throwback Tower Thursdays (TTT). The St Regis Mountain fire tower is an Aermotor tower.

We now give you Fred Knauf:

PART 1: Happy Thursday and another Throwback Tower Thursday (TTT). Today, we're going out of state and almost 700 miles west-south west of Blue Mtn. That's to Chicago, Illinois, and home of the Aermotor Corporation.

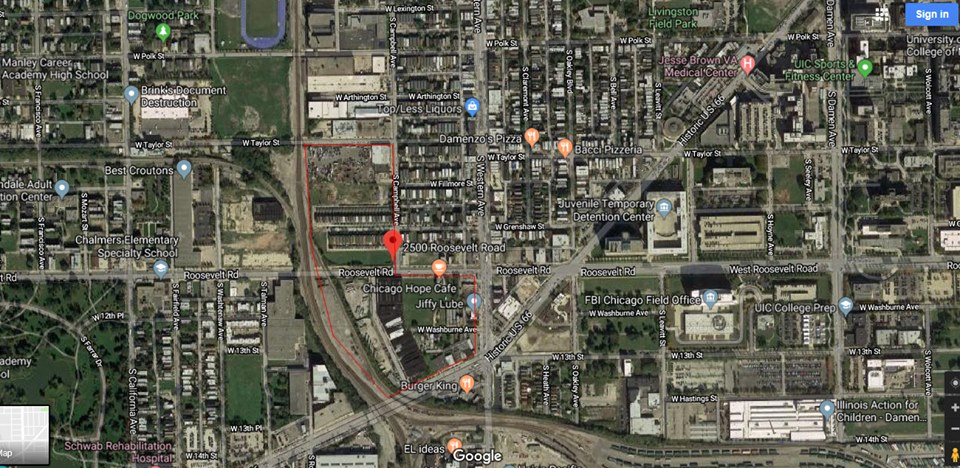

Aermotor began in 1888, a year that saw a few other industrial giants begin, including the company I've worked for since 1985, Eastman Kodak. Mr. La Verne W. Noyes formed Aermotor with one goal, to become the world's leader in windmill manufacturing for the plain’s state's farmers. Windmills were required to drive wells to bring water to the surface for livestock, home use and to some extent, irrigation of crops. Within four years, the business exploded, and the company was manufacturing over 20,000 steel windmills a year. Their manufacturing footprint, near 13th street & Roosevelt Avenue in West Chicago, grew rapidly. A train line ran from the South Chicago steel mills, and sidings were built to unload raw steel slabs & rods, and then to load onto flat cars the finished windmills for delivery to town centers along the train lines.

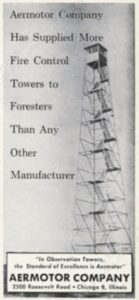

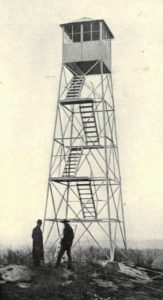

As with almost all businesses, once growth kicked in and money was flowing, consideration of expansion soon came. Around 1905, the need for forest-fire detection arose, and Aermotor was quick to toss their hat into the ring of companies manufacturing fire towers. The earliest were simple modifications to the windmill, but soon expanded designs complete with ladders instead of the windmill’s standard corner-climbers were developed, followed by designs with stairs. Aermotor offered fire tower designs from 12 to 175 feet. After their expansion into fire towers, Aermotor offered lines of towers for water tanks, viewing stands (think band-stands), but I do not believe they went into power transmission line towers like one of their largest competitors did.

As with almost all businesses, once growth kicked in and money was flowing, consideration of expansion soon came. Around 1905, the need for forest-fire detection arose, and Aermotor was quick to toss their hat into the ring of companies manufacturing fire towers. The earliest were simple modifications to the windmill, but soon expanded designs complete with ladders instead of the windmill’s standard corner-climbers were developed, followed by designs with stairs. Aermotor offered fire tower designs from 12 to 175 feet. After their expansion into fire towers, Aermotor offered lines of towers for water tanks, viewing stands (think band-stands), but I do not believe they went into power transmission line towers like one of their largest competitors did.

The New York State Conservation Commission began ordering Aermotor towers of the true fire tower design in 1915, for delivery and erection in 1916. These initial towers, called the LL-25 model, featured thinner corner angle steel and thinner cross braces, vs. the later models used in the State. Near the top of the towers, cross braces were eliminated for the use of steel rod – a throwback to the original windmill design and used to reduce the wind load on the tower. A steel ladder ran up the side of the tower (no stairs). I am not convinced that the original Bellyare Mountain & Twadell Point towers were not modified Aermotor windmill towers, but I’ve yet to find proof one way or the other.

So, when the order was placed for those towers in 1915, Aermotor would have had to order steel from those steel mills in South Chicago / Gary, Ind. areas. The raw iron for those towers would have come most likely from Northern Michigan and shipped from Escabana or Marquette, Michigan. Wouldn’t it have been great if the steel was from the Adirondack Iron Company, but by 1915 that was pretty much a ghost town / abandoned site. The steel delivered to Aermotor would have been cut, pressed, formed, stamped, drilled and then labeled with both the part ID and the tower site, forester responsible and/or delivery location. Once all the parts were allocated, they would have been carefully loaded onto a train car, almost surely a flat-bed car with all the nuts, bolts and fasteners placed into sturdy boxes fastened securely down, and that car would be taken to the yard for assembly on an east-bound train along the NY Central lines. The car with the tower would be dropped off at the closest major hub along the main line…places like Syracuse, Utica, Albany and Kingston, where the car would await a local train or removal to horse & cart for delivery. Next week, I’ll discuss delivery, tackling the job of getting the tower to the summits, and the erection process. Enjoy!

PART 2: Happy Thursday, and Happy TTT. If you’re heading to the FFLA Conference in the Catskills this weekend, please drive safe and hopefully we’ll meet. There have only been a handful of conferences in our State since 1991, so they are a thing to take in.

Last week, I provided some of the early history of the primary fire tower manufacturer of towers for New York State, the Aermotor Corporation of Chicago, Ill. Other manufactures made towers still found in other States, and one other manufacturer, International Derrick Corporation, manufactured many of the State’s towers erected by the Civilian Conservation Corp in the 1930’s.

This week I’ll be talking about how the towers got to their locations and were erected. As Assistant Superintendent of State Forests in 1918, William G. Howard wrote, “How many persons of the thousands who have seen the fire observations towers maintained by the Conservation Commission in the Adirondack or Catskill Parks, have ever stopped to consider the enormous amount of hard work required to set up these towers in place?” My hope is that this summary will give you that appreciation.

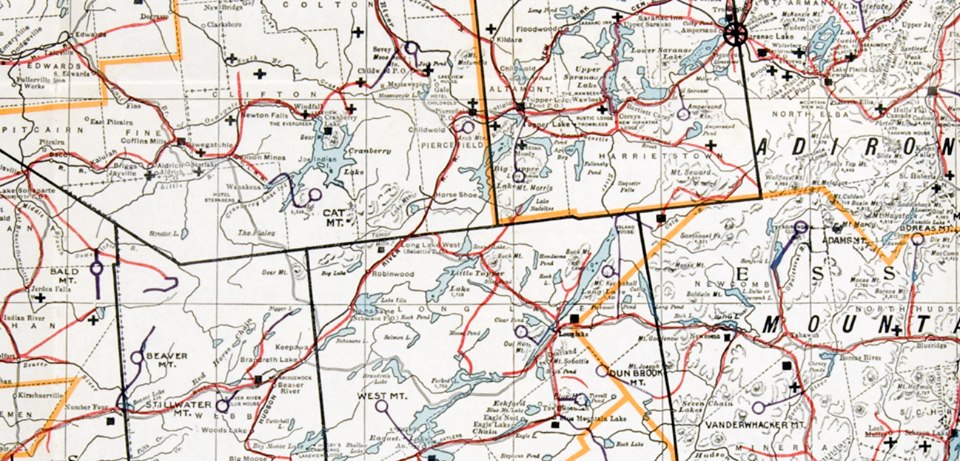

Train cars loaded with the steel and other components for the fire tower were delivered to local yards of the major cities surrounding the Parks, and from there, scheduling of the car to be taken to the closest siding on railroads that went into the Park, or to the community closest to the tower site involved both the local Ranger and the train company. Locations for delivery had to have a siding or end track that wasn’t regularly used for passing trains. By the time the car was delivered, the ranger would have allocated the labor and vehicles to move the steel from the train car and place it on the ground, inventory all the materials, then load it onto horse drawn wagons, or if the roads were good enough, delivery by the earliest of motorized trucks. For the last of these methods, there was surely a horse drawn wagon awaiting the delivery for the trip up where the good road ended. Imagine the difficulty in moving the Kempshall Mtn. tower pieces from Long Lake West (Sabbatis) down to Long Lake and then up to the mountain, or Mt. Adams or Vanderwhacker from either North Creek or Ticonderoga all the way up to the base of those mountains. What a challenge with the early roads in the mountains at that time.

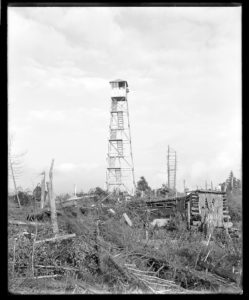

Laborers were used to clear the primitive road up the mountain from its base – wide enough to get the horses and wagon(s) through, and this would have been started ahead of the delivery. Many old logging paths were used. As they climbed, they cut. When the road became unpassable for wagons, “jumpers” were fastened to the horses and pieces mounted to this sleigh-like contraption. Onward the pulling went, and in some cases, smaller, bob-sled like sleds called “go-devils” were employed. Finally, when the sleds and horses could go no further, winches and block & tackle were used. The last line of movement was piece by piece by teams of men.

Towers did not arrive with extra pieces, so great care had to be employed that the pieces were not damaged or not lost in all the commotion of the climb. Delivery of most of the towers took many days to weeks, and during that time, the crew would set up camp around the observer camps. Battles with the elements and beavers were common.

Blueprints of the towers were provided by Aermotor, and with that the dimensions required for the mounting threaded rods that would hold the tower’s four “shoes” to which the tower was bolted. A team of men with the necessary drills, rods, mounting lead-like materials, wood for forms and concrete were sent to the planned location and the drilling of the eight holes for the rods began. Water was collected in buckets from snow melt & rain, or had to be lugged up as well. Holes were drilled up to three feet down, the rod pinned to spread the bottom section tight to the rock, and melted lead-like material or concrete poured to bond the rods and rock. Afterward, the wood frame for each footer was made and precisely leveled so that the tower would go up straight. Concrete was poured, and if all went perfectly, the footers were completed.

Once the concrete had hardened, the tower shoes were mounted to the rods and corner pieces were put up, using the angle braces to support the corner. Once a section was completed in the post 1917 models, the wood stairs and landings were added to aid in the delivery of safety boards and steel for the next level. At the top, the cab sides would be installed and then the most difficult and dangerous piece would be put on – the roof, using tied down wooden boards (planks) through the window slots. Men would climb on the boards inside, crawl out the window and stand up to place the needed bolts to hold the roof – all without the use of safety harnesses. Despite all the constant checking and care, things did not always go perfectly and at least one tower, Mt. Adams, was found to have an error in the placement of one footer which led to pieces that wouldn’t fit as the tower went up. The crew figured a way around this by loosening all the bolts, continuing to build, and then tightening when it was all together. The only problem was that the tower now had a slight spiral.

Lastly, the flag pole mount was added as were the windows. No safety mesh was ever applied to the fire towers when they were originally installed. The relief at completion must have been quite a feeling, but the next task was to pack up all the tools, sleds, etc. and move them back down the mountain. For the towers erected in the later 1930’s, the process was similar, but for the most part a little safer and a little easier as those towers were not going up onto the 3,200 to 4,100 ft. mountains. Remember, too, that weather was almost never conducive to allow the entire process to be completed without significant delays where the labor force would be tenting awaiting for the necessary break.

The tower is up, but up next are the improvements to the tower for the observer to perform his (later her) job more efficiently. That will be next week. Enjoy!

PART3: Happy TTT (for anyone new, that means Throwback Tower Thursday). Over the past two weeks I discussed the company that manufactured the earliest of the steel fire towers placed in service from 1916 through 1950, the Aermotor Corporation, and then the challenges of getting those towers to their locations. Today, I’ll discuss some of the tools built into the New York State towers to aid the observer.

Telephones and telephone lines were already strung to the observations by 1916, and it was a primary responsibility of the observer to keep those lines open and working. For many of the wooden structures, however, the phone line ended at the base of the tower in an enclosed box. That meant that the observer would have to climb down to discuss where, and what he saw. With the enclosed steel, wood and glass cab at the top of the Aermotor tower, the crank telephone could be safely attached and wires strung to the cab, greatly aiding in the interactions of observer and ranger when a smoke was detected. The phones were mounted on one of the stationary windows (each side had one stationary and one window frame which opened).

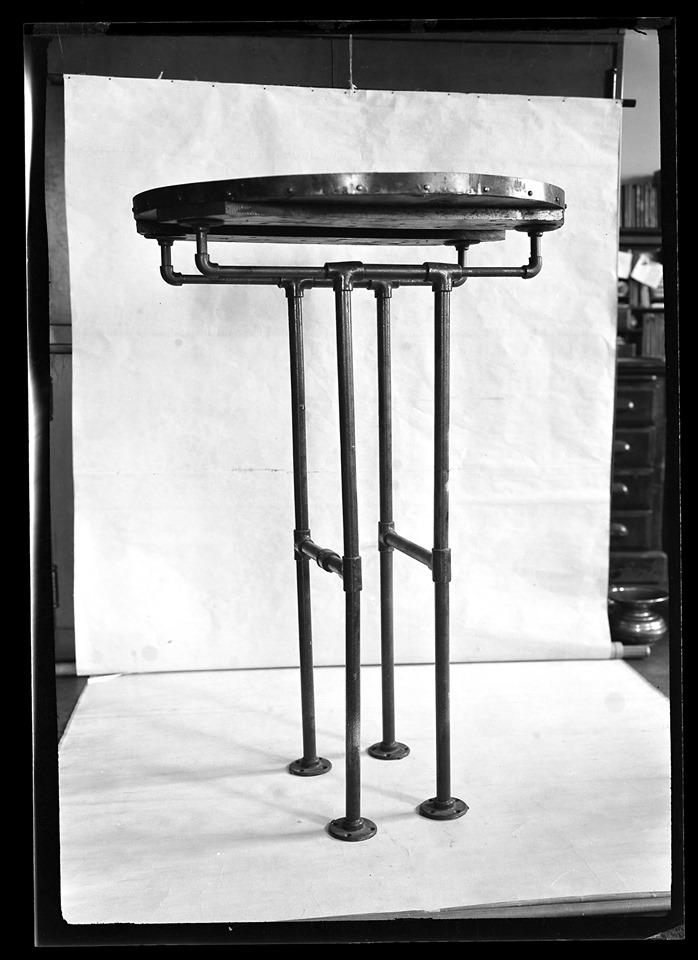

The second addition was the range map table. I’m not sure if this was an Aermotor design or one directly from the New York State Conservation Commission, but the simple table, constructed from standard household water pipe supplies was brilliant. The four legged stand supported a circular table, which could actually be shifted along parallel pipes so that the observer could look around the window frame & corners when they blocked a smoke. A number of the original tables exist today in Stillwater, Poko, and the Catskill towers, but many were thrown out or broken apart and used as railings / aids in a number of the reconstructions in recent years. Prior to this invention, the observer atop the wood tower may have a table to use to hold his map, but that was not guaranteed.

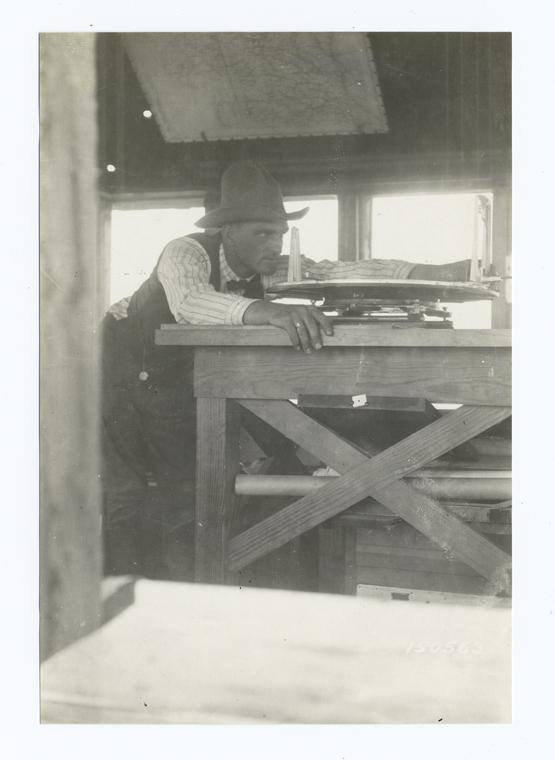

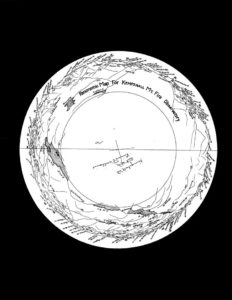

Early circular maps were provided for the observers, but by the late 19teens, a number of the original woodsmen observers were leaving the force and new men not as well versed in their knowledge of the names of the surrounding area were being employed. Kinnie Williams, soon to become the Superintendent of the Division of Lands and Forests, developed the improved topographic map table. Using a single Osborne fire-finder, which the Conservation Commission purchased, he went from tower to tower and used this sighting device to draw the panoramic display of the mountains within the viewing area of the fire tower. Each important mountain was given a numerical name on the map, and the map was scored on the boundary with the 360 degree lines. Also marked with flags were the State’s fire towers and other private towers within the station’s view. In the center, a smaller topographic map was mounted, and this was all placed under a glass surface for protection. Atop the glass was placed a metal alidade sighting device which spun around from the central pin of the map table. Using this device, a pair of binoculars, and a phone very close at hand, the observer could easily identify a location of a fire (“just behind mountain 314 and in front of mountain 1734, at 42 degrees from north”). Immediate interaction between the ranger and the observer could take place rather than multiple calls back & forth as the observer climbed back up and down to interact with what he saw.

The panoramic maps were installed into almost all of the Adirondack Mountain towers, but I’ve never heard of any going into the Catskill towers, or the few other towers up by 1922. Eventually, these too, wore out and were replaced by newer topographic map tables similar to those found in the Catskill towers.

Enjoy!