Tower Observer’s Job

In the beginning the observer’s job was centered on fire. The job was seasonal and would start in April or May, depending on funding and weather conditions, and run into the late Fall. The Observer was expected to be in the tower when conditions were right for fires. When the fire danger was low the job turned to maintenance. There was always work to be done on the phone line, the cabin or the tower itself. The phone line was checked daily to make sure there was a good connection. The Observer spent a great deal of time learning the lay of the land. The topo map on the map table was used to identify all the geographical features that were visible from the tower and to help get comfortable with the terrain. An experienced observer could pinpoint the location of smoke with just the field glasses. When smoke was spotted the observer would reach out to other towers in the area so they could get a sighting. He would then use the map table and alidade to get an azimuth reading to report the fire. The observers would then send the reading to rangers in the field. the Ranger could then use his map book to intersect lines to locate the fire.

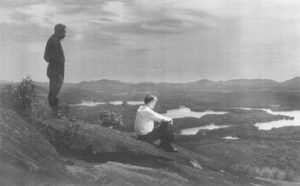

Education of the public was another constant job of the observer. The folks that climbed the mountain were treated to a wealth of information on the whole fire control system. Many observers were also well versed in the geology, flora and fauna of the area.

In later years when portable radios became available, and were being carried by the rangers in the woods, the observers – and towers – took on a new and very important role. The radios became a lifeline for not only the rangers but all DEC personnel who were working in the field. The radio system was configured to use with the radio repeater towers that were located on three mountains in the region – Whiteface, Gore, and Blue Mts. If a ranger was in an area that could reach a repeater tower with a low power portable radio, the repeater would boost the signal and broadcast it from the mountain top, thus the signal could be sent over great distances. If a signal couldn’t hit a repeater tower, chances are that no one would be able to hear him. That’s where the observers and fire towers came in. Because there were 27 fire towers in the Adirondacks you could reach one from anywhere, and usually more than one. This made the tower a vital link to communications. This then, turned into more than a safety issue. They became a dispatch center. The rangers were required to keep and maintain a “dispatch book” for their ranger district. It contained information like food vendors, lodging, fire warden lists, heavy equipment contractors, etc. A copy of these books were available in the tower which allowed the observer, with a phone and a portable radio, to handle any request the ranger had for resources on a working fire. When there were multiple fires, multiple fire towers were used which took the load off the main dispatch center using the repeater towers.

Due to the dispatch component, the responsibilities of the observer expanded to cover an important role in Search and Rescue. They were now used to call search teams, order meals and lodging and relay messages for teams in the field. As the role of the ranger changed, more duties were added to the observers. When law enforcement became a more important part of the Ranger patrol, the towers took on an even greater safety role. Tower observers would contact judges for immediate arraignments and for getting court date!

The St. Regis Mountain fire tower was in continuous use for 80 years

St. Regis Mountain Fire Tower was staffed continuously from April 1910 through 1990 making it not only the longest operating fire tower in the Adirondack Mountains, but the longest operating fire tower in the State of New York. Unfortunately for the towers, newer technologies were better at spotting fires and less expensive. In the last years of operation, the percentage of fires reported by fire tower observers dwindled to a mere 4% of all fires reported.

In 1988, the Department of Environmental Conservation concluded that towers were no longer effective and decided to phase them out of service. The 1989 plans called for staffing six to eight of the thirty one towers which were staffed in 1988. Finally in 1990, the last of the operating fire towers in New York State – including St. Regis – were closed. This brought to an end an era of organized and systematic forest fire detection that lasted 82 years.

It’s unfortunate that when the decision was made to discontinue the fire tower system it was based only on their role in fire detection. Administrators thought that they could save money and get better coverage with aircraft flying only during high fire weather conditions. The public education, dispatching capabilities, and safety aspects of the job, which had become the main focus, were not even considered.

Per Bill Starr in a FOSRMFT Facebook post: “As a former observer I can say that at each fire tower different challenges did exist. The closing of the fire towers though was strictly budgetary it had absolutely nothing to do with effectiveness as the job did expand and evolve over the years. In fact the decision to close the 5 remaining fire towers on Labor Day 1990 came from the Governor’s office. Also the airplane did not render the fire towers obsolete because by about 1992 / ’93 the aerial detection program pretty much ceased to exist for the same budgetary reasons.”

————————————————————————————————

from Adirondack Fire Towers Their History and Lore, The Northern District

By Martin Podskoch

In April 1910 a fire observer was stationed on St. Regis Mountain. When this observation station was established, no tower was erected because there was an unobstructed view due to the lack of tree cover on the mountaintop. The observer could see twelve miles to the east, fifteen miles to the south and north, and thirty miles to the west. State workers built a three-mile telephone line to the summit. The state spent a total of $294.77 to establish this observation station.

George F. Brown, the first observer, reported fifty-five fires the first year. George might have used a tent or crude cabin for shelter. By 1916 there was a cabin for the observer’s comfort.

In 1918 the state built a thirty-five-foot steel tower with a cab on the summit to give the observer a better view and provide protection from the weather.

Brighton Historian Ellen Salls shared these two newspapers stories of fires in the area near St. Regis Mountain:

“HURRICANE”

May 28, 1917 Malone Farmer

During Sunday’s hurricane the wind blew a tree across the Paul Smith’s [hydroelectric plant’s] power wire about one hundred rods from the Glass Camp on the St. Regis River and a forest fire immediately started. It was quickly seen by Albert Otis, the state observer on St. Regis Mountain, who hurriedly telephoned Ben Muncil, the fire warden. The latter was playing golf at the time, but threw down his golf sticks and rushed men to the scene. They put the fire out completely before it assumed serious proportions.

This illustrates the value of mountain observers and of the Conservation Commissioners fire-fighting system. If the fire had not been promptly placed under control much valuable property would have been involved. Both Messrs. Otis and Muncil deserve the high praise for the splendid work under difficult conditions.

FOUR OBSERVERS REPORT SAME FIRE, Threatening blaze at Jenkins Mountain is Quickly Extinguished

August 1, 1923, Adirondack Enterprise

Hundreds of campers and hotel guests in the Paul Smiths section were given a thrill Wednesday when word came of the fire burning on the south side of Jenkins mountain.

A most unusual feature of the fire was the fact that it was spotted and reported at almost the same moment by four different observers stationed on the summits of St. Regis, DeBar, Azure and Loon Lake Mountains.

The prompt alarm enabled the forest rangers and men they took with them to reach the flames in time to hold them in check until District Forest Ranger James H. Hopkins at Saranac Lake could call out a sufficient force to extinguish the fire, which was burning deep in the duff.

Despite the fact, that the fire was a mean one to handle, the force organized by District Ranger Hopkins, attacked it with such vigor that by Thursday morning the last of it had been extinguished, after having been held in an area of about one-third of an acre.

Another fire broke out Wednesday in Bloomingdale swamp and was so quickly discovered that it burned [only] about fifty square feet before being extinguished.

——————————————————————————————

The Observers

Friends: we are looking for more information on the observers. Family, friends – or the observer themselves – PLEASE submit additional information to friendsofstregis@gmail.com

1.George F. Brown (served in 1910)

George F. Brown was assigned as the first observer on St. Regis Mountain.

(The following list of Observers was taken from http://www.nhlr.org/media/2971/new_york_fire_tower_observer_roster_by_bill_starr_3-18-11.pdf)

Information on the following Observers in parentheses: (residence/start salary per month/ period of service)

2.Edward Rorke (sometimes spelled RORK) (Paul Smiths/$60/1911 May18-1911July31)

3.Harry Thompson (Paul Smiths/$60/1911 Aug1-1918 Oct31)

4.Albert Otis (Paul Smiths/$90.20/1919Apr-1928May4)

From https://localwiki.org/hsl/Albert_S._Otis

Born: 1855, a son of Joshua Otis and Amy Manning

Died: c. May 11, 1928, buried in St. John’s in the Wilderness Cemetery

Married: Mary Colby (1862-1937)

5.Edward Rorke (Paul Smiths/$100/1928May29-1931Sept21)

EDWARD RORK FIRE OBSERVER.

District Forest Ranger James H. Hopkins has announced that Edward Rork, veteran Adirondack guide and woodsman of Gabriels, has been appointed state fire observer on St. Regis mountain. He takes the place of the late Albert Otis who was found dead in his cabin several weeks ago.

It will be recalled that Edward Rork enjoyed national publicity at the time President Coolidge was at White Pine camp, after it was announced the Gabriels guide, who knows every inch of the Paul Smiths region, was to be chief guide for the presidential party.

Edward Rork has acted as observer before and District Ranger Hopkins has found his work most satisfactory.

6.Fred Lyons (Paul Smiths/$100 monthly /1932Apr-1937Oct31)

7.Leander Martin (Gabriels/$100 monthly /1938Apr-1942Oct). See Historic Saranac Lake localwiki.

8.Bert Ducatt (Saranac Lake/$100/1943Apr-1954Oct)

– from Adirondack Daily Enterprise Aug11, 1952

SERIOUS BLAZE HERE AVERTED

With the entire area being fire conscious due to the dry condition of the Adirondacks, the general 1-2- 6 alarm that sounded here Saturday afternoon, was the cause of much consternation.

The quick work on the part of the Saranac Lake Volunteer Fire Department is credited in preventing what might have been a fire of serious proportions when three acres of land’ were burned in the rear of the Duprey Cabins at Ray Brook.

News of the blaze, which started as a grass fire believed set by berry pickers, was first phoned to the department by an unidentified man working in the blowdown section near Vahl’s Cabins. The alarm was received here at 3:10 and trucks returned to the firehouse at 5:40 p.m.

The conflagration spread from grass into a brush fire and then turned to the forests. Thirteen Saranac Lake volunteers, under the direction of Fire Chief Carl Smith, were joined by Conservation Department rangers who were alerted from four area fire towers.

The first to call in was Leslie Dinsmore, at Ampersand Mt. lookout. Subsequent calls came from Bert Ducatt, at St. Regis, William Plumley, at Loon Lake, and John Wilson, Observer at Mt. Morris.

Rangers Mark Nugent, of Lake Placid, Jim Bickford, Howard Ellithorpe and Harold Parker, all of Saranac Inn headquarters of the, Conservation Department, joined in fighting the blaze. Due to the low water level in the Duprey Pond, Conservation workers had to haul their portable pump to the center of the pond for sufficient water supply.

In addition to its regular equipment the Saranac Lake street flusher was sent ot the scene and some 3,200 gallons of water were used.

Although the fire was kept clear of the 50-unit Duprey Cabin colony, both firemen and rangers . stood guard some time after the blaze had been extinguished to make sure there would be no further outbreak.

9.Carl B. Farrar (Paul Smiths/$214.47/1955Apr-1955Oct31)

– born 1886 died 1955. Buried in St. John’s Cemetery, Paul Smiths (https://localwiki.org/hsl/St._John’s_Cemetery_in_Paul_Smiths)

10.*Another source (St. Regis Mountain steward’s handbook) has J.T. Evans (1955)

11.Peter Pelkey (Lake Clear Jct./$239.47/1956May1-1961Aug9)

12.Earl Forkey (St. Regis Falls/$164.18bi-weekly/1964July30-1964Nov)

13.Meridith Anderson (male) (Malone/$128.38bi-weekly/1967Aug-1970July)

14.Steven Strack (Lake Clear/$191.39bi-weekly/1970July6-1970Nov4)

15.James A. Hathaway (Mountain View/$2.79hourly/1971May10-1971May22)

16.Gerald Noreault (Mountain View/$2.79hourly/1971May24-1971Nov9)

17.Dennis Schaffer (?/$2.79hourly/1972May18-1972Aug23)

18.Ed Samburgh (?/$2.79hourly/1973Apr-1986)

19.Bill Porter (?/?/1987)

20.Linda Lamphere (?/?/1988)

21.Patricia Finnegan (?/?/1989)

22.Dave Lamieux (?/?/1990)